In the tapestry of our daily existence, we encounter a plethora of objects and interfaces, spanning from the humble door handle to the ubiquitous smartphone, each meticulously crafted with varying degrees of efficacy. The manner in which we engage with these artifacts can range from effortless fluidity to exasperating complexity, often contingent upon the design principles imbued within them.

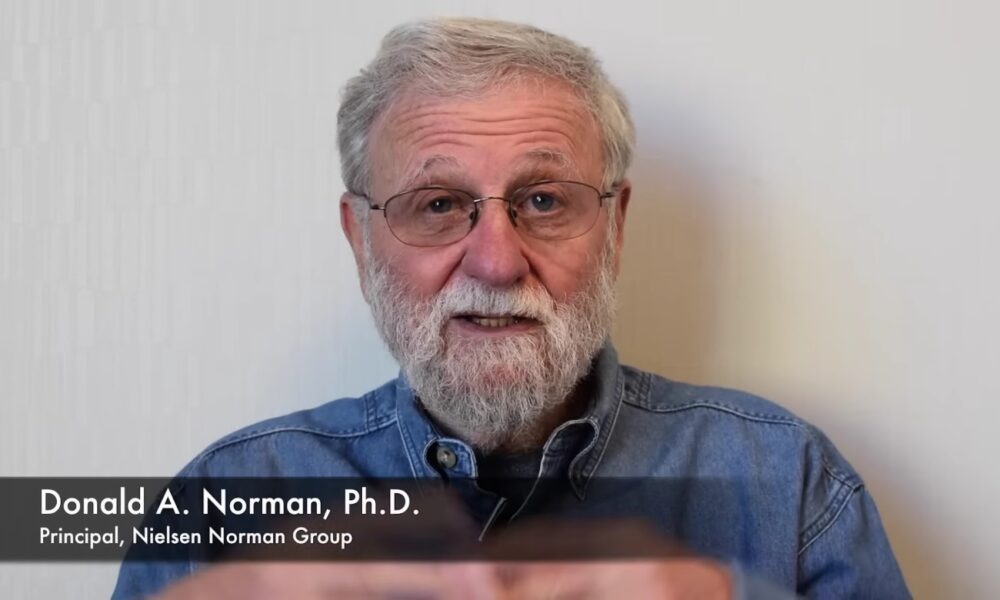

Renowned cognitive scientist and usability engineer Don Norman, in his seminal opus “The Design of Everyday Things,” delves into the intricate realm of design, shedding light on its profound impact on our interactions and experiences.

Within the pages of Norman’s work lie a profound exploration of design’s role, from the discernment of affordances and signifiers to the repercussions of feedback loops and constraints, all of which shape our quotidian rituals.

This synopsis serves as a passage through the foundational tenets elucidated in “The Design of Everyday Things,” distilling Norman’s insights into actionable takeaways. We embark on a voyage to uncover the mysteries underpinning the design of commonplace objects, revealing the transformative potential embedded within thoughtful design to enrich our lives and redefine our surroundings.

Chapter 1: Unveiling the Psychology Behind Everyday Design

In the realm of design, it’s not merely about the aesthetics; it’s about how things operate, how users interact with them, and the seamless harmony between people and technology. Delving deeper into the intricacies of design, two fundamental pillars emerge: discoverability and understanding.

Discoverability: Navigating Possibilities

When faced with a new device or system, users embark on a journey of discovery. Can they easily discern the available actions? Discoverability hinges on intuitive clues that guide users effortlessly through the interface. Here’s how designers ensure discoverability:

- Visible Signals: Incorporating visual cues that instinctively direct users. For instance:

- Utilizing a vertical plate to indicate the direction of push for doors;

- Making supporting pillars visible to signify points of interaction;

- Striking a Balance: While aesthetics are crucial, functionality takes precedence. Designers must ensure that visual elements serve a purpose beyond mere adornment.

Understanding: Deciphering Meaning

Beyond discoverability lies the realm of understanding. Users seek answers to questions like: How does this device work? What do the controls signify? Designers must bridge this gap by crafting interfaces that speak a universal language of usability.

Manuals and Instruction: In complex systems, manuals act as guides, unraveling the intricacies for users. Yet, the ideal design strives for intuitive understanding, minimizing reliance on supplementary materials. Also, discover insights from “The Coddling of the American Mind” with this engaging summary. Uncover its impact and relevance in today’s society.

Expanding the Definition of Design:

Design transcends physical structures; it permeates every facet of human interaction. From the layout of a room to the workflow of a business, design shapes our experiences. Major design fields encompass:

- Industrial Design: Focusing on product development with a user-centric approach;

- Interaction Design: Enhancing user understanding and engagement with technology;

- Experience Design: Crafting memorable experiences across various touchpoints.

Human-Centric Design: A Paradigm Shift

Recognizing that tools exist for human use, designers adopt a human-centric lens. They acknowledge the quirks of human behavior and design with empathy, embracing imperfections. Key facets of human-centric design include:

- Understanding Human Behavior: Designers must grasp the intricacies of human psychology, catering to both rational and irrational tendencies;

- Acceptance of Errors: Designing with the assumption that users will make mistakes fosters resilience in the face of human fallibility.

The Essence of Human-Centered Design (HCD):

HCD is more than a methodology; it’s a philosophy rooted in empathy and user advocacy. By aligning design with user needs and capabilities, HCD seeks to create meaningful experiences. Its core tenets include:

- Experience Enhancement: Elevating user interactions from mundane tasks to delightful experiences;

- Cognitive and Emotional Harmony: Recognizing the intertwined nature of cognition and emotion in user experiences.

Deciphering Discoverability: The Five Key Elements

- Affordances: Determining the actions made possible by an object or system;

- Signifiers: Communicating where and how actions should occur;

- Constraints: Limiting factors that guide user behavior and form conceptual models;

- Mappings: Establishing spatial correspondences between controls and actions;

- Feedback: Providing timely responses to user actions, fostering a sense of control and understanding.

Conceptual Models: Bridging Understanding

Conceptual models serve as mental blueprints, guiding users through the intricacies of a system. A well-crafted conceptual model empowers users to predict outcomes and navigate with confidence. Key considerations include:

- Clear Signifiers: Ensuring that visual and auditory cues align with user expectations;

- System Image: Curating a holistic understanding through documentation, labels, and physical structure.

Navigating Design Challenges:

Designers grapple with a myriad of constraints, from budgetary limitations to technological constraints. Balancing human-centered design with competing demands requires finesse and strategic alignment. By prioritizing user experience alongside other imperatives, designers can create products that resonate deeply with users while meeting business objectives.

Chapter 2: Understanding Everyday Actions: The Psychology Behind Interaction

In the realm of everyday actions, whether it’s using a product, a tool, or a service, individuals often encounter two significant challenges: the Gulf of Execution and the Gulf of Evaluation. These gulfs represent the gaps between the desired outcome and the available options. Let’s delve deeper into understanding these psychological nuances and how they influence our interactions:

The Gulf of Execution

When faced with the Gulf of Execution, users grapple with questions like “How do I work this thing?” or “What actions can I perform with it?” This obstacle is bridged through various elements such as signifiers, constraints, mappings, and conceptual models. Here’s a breakdown:

- Signifiers: These are cues or indicators that convey how a product or service should be used;

- Constraints: Limitations or restrictions that guide users towards appropriate actions;

- Mappings: The relationship between controls and their resulting actions;

- Conceptual Model: The mental framework users construct to understand how a system functions.

The Gulf of Evaluation

On the other hand, the Gulf of Evaluation involves questions like “What happened?” or “Is this what I wanted?” Feedback mechanisms and conceptual models play crucial roles in bridging this gap. Here’s how:

- Feedback: Continuous information provided by the product or service about its state and the outcomes of actions taken;

- Conceptual Model: Users’ mental representations of the system and how it should behave.

The Action Cycle: Understanding Human Behavior

The action cycle encompasses seven stages, each crucial in understanding human behavior and interaction with products or services:

- Goal Formation: Defining the desired outcome;

- Planning: Devising the necessary actions to achieve the goal;

- Specification: Detailing the sequence of actions;

- Execution: Performing the specified actions;

- Perception: Observing the state of the world;

- Interpretation: Making sense of the perception;

- Comparison: Evaluating the outcome against the initial goal.

Types of Behaviors

Human behavior can be categorized into different types based on its driving force:

- Goal-driven Behavior: Starting from the top of the action cycle and working downwards, driven by predefined objectives;

- Event-driven Behavior: Initiated by external triggers or environmental stimuli, often starting from the evaluation stage.

Root Cause Analysis: Uncovering True Goals

Delving deeper into users’ motivations beyond superficial goals is essential for effective design. By reconsidering the underlying objectives, designers can create more intuitive and impactful solutions. For instance, Professor Theodore Levitt’s famous quote highlights the importance of understanding the true intent behind user actions.

The Psychology of Design

Designers must comprehend the intricacies of the human mind to create user-centric experiences. Emotions play a significant role in decision-making and perception, working hand-in-hand with cognitive processes. Understanding the different systems of cognition—subconscious, conscious, and reflective—helps in crafting designs that resonate with users on multiple levels.

- Systems of Cognition

- Subconscious: Fast and automatic processing, responsible for immediate perceptions and rapid decision-making;

- Behavioral: Learned skills handled at a subconscious level, guided by past experiences and habits;

- Reflective: Deep, analytical cognition involved in complex decision-making and long-term memory formation.

- The Role of Conceptual Models: Conceptual models, akin to storytelling, shape users’ understanding of the world. However, these mental representations can sometimes be flawed, leading to misconceptions or naive theories. Recognizing and addressing these misconceptions is crucial for effective design.

Assigning Blame and Understanding Errors

Humans tend to seek causes for events and assign blame when things go wrong. This inclination influences how individuals perceive errors and their interactions with technology or products. Designers must anticipate and mitigate potential errors by making systems easy to detect, with minimal consequences and reversible effects.

Design Principles for Seamless Interaction

To facilitate smooth user interaction, designers should adhere to fundamental principles:

- Discoverability: Ensuring users can easily discern available actions;

- Feedback: Providing clear and continuous information about the system’s state;

- Conceptual Model: Projecting a clear understanding of how the system operates;

- Affordances: Designing elements that suggest possible actions;

- Signifiers: Using cues effectively for discoverability and feedback;

- Mappings: Establishing intuitive relationships between controls and actions;

- Constraints: Implementing physical, logical, semantic, and cultural constraints to guide users’ actions.

Chapter 3: Exploring Knowledge Integration in Human Behavior

In the intricate dance of human cognition, knowledge is not confined solely to the mind but is intricately interwoven with the world around us. This dynamic interplay manifests in various ways, shaping behaviors, decisions, and perceptions.

Knowledge in the Head and the World:

Understanding how knowledge resides both internally and externally provides insights into how individuals navigate their surroundings and accomplish tasks. Here’s how it unfolds:

- Head: This encompasses the knowledge stored within the individual’s mind, including memories, skills, and learned information;

- World: External sources such as the environment, cultural norms, and tools serve as extensions of knowledge, enabling individuals to derive solutions and adapt to different contexts.

Natural Constraints and Cultural Conventions:

Within this intricate web of knowledge, natural constraints inherent in the environment and cultural conventions embedded in society influence behavior and decision-making processes:

- Natural Constraints: These are the inherent limitations and affordances present in the physical environment, shaping the way tasks are approached and executed;

- Cultural Conventions: Embedded within the individual’s cognitive framework are societal norms, traditions, and etiquettes that guide behavior and interaction within a cultural context.

Maximizing Efficiency through Knowledge Integration

The fusion of internal and external knowledge facilitates efficient decision-making and task execution. By leveraging both mental faculties and environmental cues, individuals optimize their cognitive processes:

- Minimizing Learning Burden: The integration of internal and external knowledge minimizes the need for exhaustive learning by providing readily available resources and cues;

- Organizing the Environment: Deliberate structuring of the environment can enhance behavioral outcomes by aligning external cues with internal knowledge frameworks.

Examples:

In the smartphone era, individuals rely less on memorizing phone numbers, utilizing external resources such as contact lists for efficient communication. Recognition of coins relies on generalized features rather than precise details, showcasing the integration of internal and external knowledge in everyday tasks.

Exploring Types of Knowledge

Diving deeper into the realms of cognition unveils distinct categories of knowledge, each serving unique functions and processes:

- Declarative Knowledge (“Knowledge of”): This encompasses factual information and explicit rules that can be articulated and transmitted through various means;

- Procedural Knowledge (“Knowledge of How”): Unlike declarative knowledge, procedural knowledge pertains to skills and know-how, often acquired through practice and demonstration.

Memory and Decision Making:

Memory plays a pivotal role in integrating knowledge and informing decision-making processes. Understanding the nuances of memory can elucidate cognitive mechanisms:

- Short-term Memory (STM): Holding transient information in consciousness, STM serves as a temporary workspace for cognitive tasks, albeit with limited capacity and susceptibility to distractions;

- Long-term Memory (LTM): Housing vast repositories of past experiences and knowledge, LTM provides a reservoir for retrieval and utilization, albeit with challenges such as retrieval difficulties.

Harnessing Simplified Models and Conceptual Frameworks

Simplified models and conceptual frameworks serve as cognitive tools, enabling individuals to navigate complex information landscapes and make informed decisions:

- Simplified Models: These abstractions distill complex phenomena into manageable frameworks, facilitating understanding and problem-solving in real-world contexts;

- Conceptual Models: While not necessarily accurate representations, conceptual models offer explanatory power and guide behavior, aligning actions with desired outcomes.

Example:

The simplified model of STM, though not scientifically precise, aids in understanding cognitive processes and can inform design decisions for user interfaces and educational materials.

By unraveling the intricate interplay between internal and external knowledge, we gain deeper insights into human cognition and behavior, paving the way for more effective learning strategies, decision-making frameworks, and design interventions.

Chapter 4: Understanding Constraints: Enhancing Problem-Solving Skills

Constraints serve as guiding clues, shaping the realm of feasible actions in various contexts. By recognizing and navigating through different types of constraints, individuals can streamline decision-making processes and optimize outcomes. Here are four distinct categories of constraints:

- Physical Constraints: Physical limitations dictate the feasible range of operations. Examples include:

- Shape Compatibility: Square pegs fitting into square holes, while round pegs fit into round holes;

- Size Restrictions: Objects of specific dimensions fitting into corresponding spaces.

- Cultural Constraints: Cultural norms and practices define acceptable behaviors within a society. Key points to consider:

- Color Symbolism: Red often signifies “stop” in many cultures, illustrating a culturally accepted constraint;

- Eating Habits: Variations in utensil usage, such as forks, chopsticks, or hands, reflect cultural constraints in dining practices.

- Semantic Constraints: Meaning-driven constraints rely on contextual significance to guide actions. Examples encompass:

- Functional Placement: Placing a windshield in front of a rider to block wind, aligning with its semantic purpose;

- Purposeful Arrangement: Organizing items based on their intended use or function.

- Logical Constraints: Logical reasoning establishes constraints by deducing relationships between elements. Notable instances include:

- Control Associations: Linking specific controls to corresponding functions logically. For instance, left switches controlling left lights and vice versa;

- Sequential Operations: Following logical sequences to perform tasks efficiently.

Legacy Problems: Addressing Challenges in Innovation

Legacy issues encompass existing standards or practices that hinder the adoption of new solutions. Considerations include:

- Standard Ambiguity: Symmetrical cylindrical batteries, which lack clear orientation, pose challenges for new designs;

- Resistance to Change: Prevailing norms or habits may resist the adoption of innovative alternatives.

Leveraging Design Principles: Enhancing User Experience

Affordances, signifiers, mappings, and constraints collectively shape user interactions with products and technologies. Key insights include:

- Affordances: Designing interfaces that intuitively suggest their potential uses to users;

- Signifiers: Incorporating visual or auditory cues to guide users’ actions effectively;

- Mappings: Establishing clear relationships between controls and their corresponding functions;

- Constraints: Utilizing constraints to simplify decision-making processes and enhance usability.

Embracing Innovation: Beyond Skeumorphism

While skeumorphism initially bridges familiarity with novelty in technology, embracing innovation entails transcending outdated paradigms. Key considerations include:

- Functional Evolution: Prioritizing functional relevance over aesthetic familiarity in design;

- User-Centric Approach: Aligning technological advancements with users’ evolving needs and preferences;

- Iterative Design: Continuously refining design paradigms to optimize user experience and adapt to changing contexts.

By understanding and effectively navigating constraints, designers and innovators can foster enhanced problem-solving skills, promote innovation, and elevate user experiences in various domains.

Chapter 5: Reframing Human Error as Design Challenges

Designers often overlook mental limitations while meticulously addressing physical constraints. However, understanding human cognition is pivotal in crafting effective systems.

- Holistic Approach: Design processes should encompass both physical and mental limitations;

- User-Centric Design: Prioritize human requirements alongside system and hardware needs;

- Psychological Considerations: Incorporate insights from cognitive psychology to inform design decisions.

Embracing the Swiss Cheese Model of Accidents

James Reason’s Swiss cheese model offers a profound perspective on accidents, emphasizing the convergence of multiple failures.

- System Redundancy: Implement backup mechanisms to mitigate single points of failure;

- Continuous Improvement: Iterate designs to address identified weaknesses and potential failure points;

- Proactive Risk Management: Anticipate potential failure scenarios and preemptively address them in the design phase.

Unpacking Root Causes with the Five Whys

The Five Whys technique, borrowed from Toyota’s problem-solving methodology, encourages deep exploration to uncover underlying causes.

- Thorough Investigation: Delve beyond surface-level explanations to unearth systemic issues;

- Iterative Inquiry: Persist in asking “why” to peel back layers of causation and uncover root factors;

- Preventive Measures: Design interventions based on identified root causes to forestall recurrence.

Understanding Human Errors: Slips vs. Mistakes

Distinguishing between slips and mistakes provides invaluable insights into human behavior and informs design considerations.

- Slips Prevention: Design interfaces to minimize the occurrence of action-based errors;

- Mistakes Mitigation: Provide clear guidance and feedback to users to prevent rule-based errors;

- Design Foresight: Anticipate potential slip and mistake scenarios during the design phase to proactively address them.

Addressing Social Pressures and Environmental Factors

External pressures and situational contexts can significantly influence human behavior, necessitating design solutions that account for social dynamics.

- Ethical Design: Consider the ethical implications of design decisions, particularly in high-stakes environments;

- Stress Management: Incorporate features to alleviate user stress and mitigate decision-making biases;

- User Empowerment: Equip users with tools and resources to navigate social pressures and environmental constraints effectively.

Leveraging Checklists for Error Prevention

Checklists serve as invaluable tools for error prevention and accuracy enhancement, fostering a culture of safety and reliability.

- Cognitive Aid: Offload cognitive burden by providing structured prompts for task execution;

- Collaborative Approach: Foster collaboration by encouraging shared checklist usage among team members;

- Continuous Improvement: Regularly review and refine checklists based on user feedback and evolving needs.

Fostering a Culture of Error Awareness and Improvement

Creating a culture that embraces error awareness and continuous improvement is essential for enhancing system reliability and user safety.

- Transparency: Foster an environment where users feel comfortable reporting errors without fear of reprisal;

- Data-Driven Decision Making: Leverage data insights to inform design iterations and error reduction strategies;

- Learning Organization: Cultivate a culture of learning and adaptation, where mistakes are viewed as opportunities for growth and improvement.

By reframing human errors as design challenges and adopting a proactive approach to error prevention, designers can create systems that are more resilient, user-friendly, and error-tolerant.

Chapter 6: The Art of Design Thinking

In the realm of consulting and problem-solving, a fundamental principle reigns supreme: never tackle the surface problem head-on. More often than not, the apparent issue is merely a symptom of a deeper, more intricate challenge lurking beneath the surface. Rushing to solve without questioning the essence of the problem can lead to misguided efforts and wasted resources.

Embrace the Habit of Problem Exploration:

- Question Assumptions: Challenge the assumption that problems present themselves neatly packaged. Delve deeper to uncover the underlying complexities;

- Think Beyond the Surface: Recognize that problems are multifaceted and require thorough exploration to discern the true root cause;

- Utilize Design Thinking: Embrace the iterative process of design thinking to unearth the real issues before seeking solutions.

The Double-Diamond Model of Design:

Navigating the design landscape demands a structured approach that balances problem exploration and solution discovery. The Double-Diamond Model offers a roadmap, consisting of two distinct phases:

- Problem Identification: Embark on a journey to discover the crux of the issue, expanding thinking to explore underlying complexities;

- Solution Crafting: Once armed with insights, embark on a quest for solutions, exploring a plethora of possibilities before converging on the optimal answer.

Key Features:

- Expanded Thinking: Each phase involves extensive research and ideation to broaden perspectives and explore diverse solutions;

- Iterative Process: The model emphasizes iteration, allowing for refinement and enhancement of ideas over time.

The Iterative Cycle of Human-Centered Design:

At the heart of human-centered design lies an iterative cycle, often likened to a spiral method. This cyclical approach encompasses several key stages:

- Observation: Immerse yourself in the world of the user, keenly observing behaviors and uncovering latent needs;

- Idea Generation: Foster creativity by generating a myriad of ideas, pushing boundaries without restraint;

- Prototyping: Translate ideas into tangible prototypes, embracing simplicity and functionality;

- Testing: Engage users in testing prototypes, gathering feedback to refine and improve designs.

Effective Practices:

- In-depth Research: Conduct qualitative research to gain profound insights into user needs and behaviors;

- Creative Ideation: Encourage wild ideas and unconventional thinking to unlock innovative solutions;

- User-Centric Testing: Involve users throughout the design process, ensuring solutions meet their needs and preferences.

Activity-Centered Design:

Shifting the focus from individuals to activities, activity-centered design offers a holistic approach to product development. By understanding the broader context of user activities, designers can create solutions that resonate universally.

Key Concepts:

- Activity vs. Task: Distinguish between high-level activities and lower-level tasks, focusing on the holistic user experience;

- Hierarchy of Goals: Align design objectives with user goals, addressing overarching motivations and specific actions.

The Challenges of Design Management:

While the design process holds promise, navigating its complexities poses formidable challenges. From managing interdisciplinary teams to accommodating diverse constraints, effective design management requires finesse and adaptability.

Overcoming Challenges:

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Foster collaboration among diverse disciplines, fostering mutual understanding and respect;

- Navigating Constraints: Address conflicting requirements and design for diverse user needs, embracing inclusivity and accessibility.

Chapter 7: Navigating Design Dynamics in the Business World

In the dynamic landscape of business, product innovation manifests in two distinctive forms, each with its own allure and challenges:

- Incremental Innovation:

- Commonly seen and less flashy, incremental innovation involves making gradual improvements or additions to existing products or services;

- Often driven by feedback loops from users and market demands, incremental innovation aims at enhancing existing offerings without radically altering them;

- Examples include software updates, minor feature additions, or slight design modifications aimed at refining user experience.

- Radical Innovation:

- Bold and disruptive, radical innovation ventures into uncharted territories, challenging conventional norms and paradigms;

- While less common, radical innovations have the potential to revolutionize industries when successful, leading to transformative changes in consumer behavior and market dynamics;

- Notable examples include the introduction of the personal computer, the internet, or the smartphone, which fundamentally reshaped how society interacts with technology.

Key Competitive Dimensions in Design

In the fiercely competitive arena of business, design decisions play a pivotal role in shaping product success. Several fundamental dimensions drive competitive differentiation:

- Price:

- The cost of a product or service relative to its perceived value influences consumer purchasing decisions and market positioning;

- Striking a balance between affordability and profitability is crucial for sustainable business growth.

- Features:

- The breadth and depth of features offered contribute to product utility and customer satisfaction;

- However, a careful balance must be maintained to avoid “featuritis,” where excessive features overwhelm users and dilute the core value proposition.

- Quality:

- Quality encompasses reliability, durability, and overall performance, reflecting the product’s ability to meet or exceed user expectations;

- Maintaining high quality is essential for building brand trust and fostering customer loyalty.

- Speed:

- Rapid development cycles and timely product launches are imperative in dynamic markets where agility is paramount;

- Accelerated timelines exert pressure on design and development teams to deliver innovative solutions without compromising quality or reliability.

Mitigating Feature Creep: A Strategic Imperative

“Feature creep,” also known as “featuritis,” poses a significant challenge to product design and development. This phenomenon occurs when products accumulate unnecessary features, complicating the user experience and diminishing the original simplicity and elegance. Several factors contribute to feature creep:

- Customer Demands: Existing customers often request additional features and functionalities, driving continuous product expansion;

- Competitive Pressures: Rival companies introduce new features, compelling competitors to match or surpass these offerings to remain competitive;

- Market Dynamics: In saturated or stagnant markets, adding new enhancements becomes a strategy to stimulate demand and encourage product upgrades.

To combat feature creep and foster innovation, companies can adopt a strategic approach that emphasizes:

- Focus and Prioritization: Identify and prioritize areas of strength and differentiation, allocating resources to enhance these core capabilities rather than blindly imitating competitors;

- Customer-Centricity: Shift focus from competition-driven to customer-driven innovation, aligning product development efforts with the genuine needs and preferences of end-users;

- Resilience to Technological Change: Acknowledge the rapid pace of technological evolution while recognizing the enduring influence of human behavior and cultural dynamics on product adoption and acceptance.

Navigating Innovation Dynamics in Business Ecosystems

In the realm of business, innovation strategies vary between large corporations and small enterprises:

- Large Companies:

- Characterized by conservatism, large corporations often exhibit risk-averse tendencies, prioritizing incremental improvements over radical innovations;

- The high failure rate associated with groundbreaking ideas necessitates a cautious approach to experimentation and adoption.

- Small Companies:

- Small enterprises possess greater flexibility and agility, enabling them to embrace experimentation and pursue radical ideas with relatively lower risk;

- Embracing a culture of innovation allows small businesses to leverage disruptive technologies and carve out niches in competitive markets.

Unveiling the Origins of Innovation: Stigler’s Law

Stigler’s Law highlights the phenomenon where ideas and innovations are often attributed to famous individuals, overlooking the contributions of lesser-known pioneers. For instance:

- The concept of multitouch and touchscreen controls predates the smartphone revolution, with earlier iterations paving the way for subsequent advancements;

- Acknowledging the evolutionary nature of innovation underscores the collective efforts and contributions of numerous innovators across generations.

The Evolution of Technology and Democratization of Design

Advancements in technology have democratized the design process, empowering individuals to unleash their creativity and innovation:

- Self-publishing platforms, 3D printing technologies, and online video creation tools have democratized access to creative expression and product development;

- The proliferation of accessible design tools and resources has led to a surge in individual innovation, catalyzing diverse forms of creativity across various domains.

Conclusion

In conclusion, “The Design of Everyday Things” offers a compelling narrative that underscores the significance of design in shaping our daily interactions and experiences. Through the exploration of key concepts such as affordances, signifiers, feedback loops, and constraints, Don Norman provides readers with invaluable insights into the intricate world of design. By understanding these principles, we can enhance our ability to create intuitive, user-centric designs that seamlessly integrate into our lives.

As we reflect on Norman’s work, we are reminded of the profound impact that thoughtful design can have on society as a whole. From simplifying everyday tasks to fostering greater accessibility and inclusivity, well-designed objects and interfaces have the power to transform our world for the better.

Moving forward, let us embrace the lessons gleaned from “The Design of Everyday Things” as we continue to innovate and iterate in the realm of design. By prioritizing usability, functionality, and user experience, we can create a future where every interaction is a seamless and enriching experience.